The responsibility to develop family business fell on Alexandr Sergeyevich Stroganov, a 24-year-old baron. By that time, the heir got brilliant education, which included a serious study of industrial plants in Europe. Alexander Sergeevich, considering a proposal made by the manager Fyodor Vaulin and relying on his elder uncle's successful experience – Alexander Grigoryevich Stroganov built the Yugo-Kamsky Plant in 1746 – decides to build a plant in the forested area of the modern Ocher. A great deal of charcoal was required to make bloomery hearths for the hammering plant. All they had left to do is to build a new town around the plant in a nook of a huge domain.

History

History of Ocher Machine-building Plant

In 1759, it was officially decided to build the plant. At the request of Alexandr Sergeyevich Stroganov, the permission to build an ironworks was obtained from the Empress Elizabeth. By her decree of June 7, 1759, on an uninhabited area at the confluence of four small rivers - Ocher, Duzhkovka, Berezovka and Travnaya, 5 kilometres from the village of Luzhkovo, the construction was started. In the beginning, barracks were built for workers and houses for employees. Savin, a dammer from the village of Dobryanka, ran the deforestation and the damming. After that the walls of hammering factories and fur houses were erected; machines, foundry air furnaces and bloomery hearths were set. For the general supervision, Alexey Pryadilshchikov from the village of Dubrovskoye, a serf, was appointed a warden. Damming was the most exhausting part. At the time, this dam was one of the biggest waterworks in the Urals region. The ground for the dam was dug manually from the slope of the Kokuy mountain, carried on shoulders, carted on wheelbarrows.

In 1761, the production was launched. The history of the plant dates from that time. It was reported to Alexandr Sergeyevich Stroganov that four iron-forging hammers were launched. The cast iron from which iron was produced, was delivered from the Bilimbay (the modern Sverdlovsk Oblast) plant by floating on baidarkas during spring tide down the rivers Chusovaya and Kama to the Tabory pier. There serfs reloaded it and delivered to the plant by animal-powered transport. In total, 181 people worked at the plant: house serfs, servants, craftsmen and working men.

Kopan is an artificial channel that connects the rivers Cheptsa and Ocher. In the beginning of the 19th century Count Stroganov's ironworks that received energy from water, faced with problems. It was decided to transfer some of the waters from the river Cheptsa to the Ocher Pond through deep digging for a more stable replenishment of the water. It was made by efforts of serfs in 1813-1814.

In 1814, Ignatyev was appointed a new police district councillor. The Stroganovs entrusted the management of all their possessions to the police district councillor Ignatyev, as he was highly experienced in mining and metallurgy. Ignatiev made detailed plans for the work of Ocher and Pavlovsky plants. The plans provided for the overall size of production, standards and salaries for serf craftsmen, which depended on the cost of production and market prices for commodity iron.

In 1840, the construction of stone workshops was started. Komarov, one of the most talanted architects from the Urals, designed stone workshops for the Ocher plant, including bloomery, turning and others. Moreover, the planning took into account the organization of the production process, reducing the path of production, creating convenient work conditions and cutting costs. The construction was finished in 1844. This was a hard work. The shift duration was up to 16 hours or even more. The workers were punished for offences and sabotage with severity.

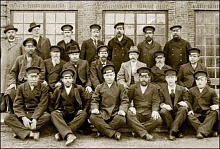

In 1913, buildings of the Ocher plant were rented by Okhansk Zemstvo (zemstvo was an institution of local government), and a showpiece workshop for the production of agricultural machines and weapons was founded instead. There were threshers, grenades, axles and hubs for artillery gigs, diaphragms and shrapnel shells, wire cutters, clutches, anvils and the like.

On 1 October 1922, the plant was renamed as the State Plant No. 5. It specialized in the production of agricultural machinery. The production output of the state plant was 50 sets per month. Besides, manure spreaders, hay balers, flax decorticators, flax pullers, hydraulic pumps, strawmills and other agricultural products were manufactured. In 1922, American Fordson tractors passed along Torgovaya street (nowadays – Lenin street) near a local shop in an act of protest. Today, a memorial tablet associated with the events is set at this place.

In 1969, the first batch of sucker rods was produced. Production facilities allowed to produce up to 300,000 sucker rods per year.

In the 1970–80s, the plant was being extensively reconstructed. The second workshop for sucker rod production was being constructed. Due to the plant reconstruction, gas supply for the town of Ocher was provided, as the equipment applied at the enterprise ran on gas. People worked for at least 12 hours a day. According to the plan, the plant had to produce one million sucker rods per year.

In the 1980s, the plant began to solve housing problems, and the construction of houses for plant workers was started. The more houses they built, the more new houses was required. In 1984, the number of the plant workers was about 1,500. The plant was like a big family for many of them, and some people even formed dynasties of the plant workers.

The 1990s were a troubled time. The production output decreased significantly. The decline of the plant was noticeable: there were constant job cuts. Many people doubted if the plant could survive. Nonetheless, the plant continued the housing construction. Yet, because of insufficient funds, many projects had to be closed, and a number of houses remained unfinished.

A proprietory solution by OMBP was introduced – an exclusive technology for the restoration of sucker rods. Only for half a year of cooperation with Udmurtneft LLC (a division of NK Rosneft OAO), the order volume for the restoration of spent sucker rods grew from 1670 to 3500 units that passed the whole technological cycle of production.